Unprecedented Effects: How the Hospitality Industry Will Recover

5 Min Read By Lee D. Mackson, Michelle G. Hendler

There is no doubt that COVID-19 has had an unprecedented effect on the economy in general and the way people live their daily lives. While it appears that every industry has been affected, some sectors have been hit harder than others, each with its own unique set of circumstances. The hospitality industry is no exception and it appears as if there are both good times and bad times ahead. In the short run, COVID-19 has taken a significant bite out of the hospitality industry, but there does appear to be some light at the end of the tunnel.

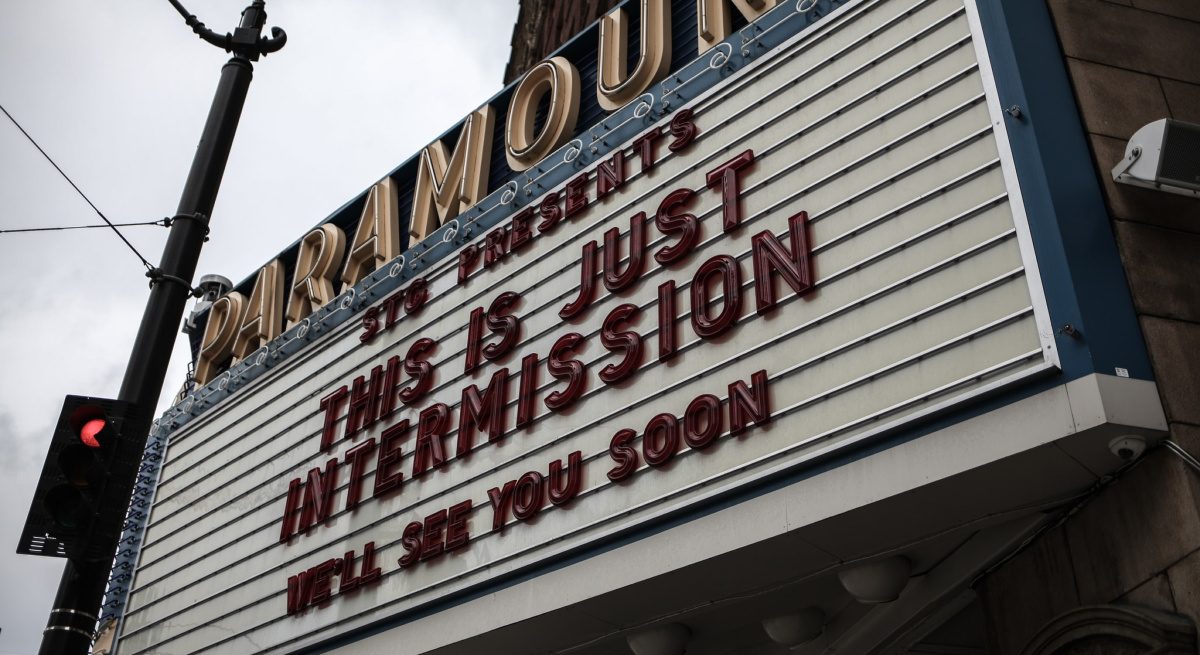

Hospitality was one of the first and hardest hit industries by the pandemic because the industry is leisure-driven and largely funded by discretionary spending. The current situation Involving lack of travel, dining out, and attending live entertainment, including sporting events, is of course having an adverse impact on hotels, restaurants and entertainment venues. Moreover, many states and/or counties are under “stay at home” orders where hotels are shut down and restaurants are only permitted to offer take-out or delivery to their patrons.

At this point, the hospitality industry is basically in “survival mode." In fact, as Forbes recently noted, only about 33 percent of Americans say they are willing to stay in a hotel and only 28 percent will be ready to fly within three months of the curve flattening. Only one in six Americans say they will stay in a hotel within a month of COVID-19 being curtailed, and slightly more than half of Americans (52 percent) have expressed a willingness to stay in a hotel within six months.

Restaurants of all sizes have also been hit hard. Chain restaurants as well as small, “family owned” restaurants are all struggling to pay rent and survive. In fact, some restaurants and retailers went so far as to not pay the April rent or debt service altogether. Some franchisors are trying to work with franchisees on reduced or eliminated franchise fees. Regardless of size, restaurants, if operating at all, are offering incentives and discounts on take-away/delivery orders. Most larger restaurants will likely re-open but almost certainly will do so with reduced staffing and occupancy limitations. The smaller restaurants may never re-open, depending on capital and expenses. All in all, even when things are back to “normal,” people will be reluctant (at least initially) to put themselves in any setting that involves close proximity to others and/or discretionary spending.

Compounding the problem is the fact that the pandemic has resulted in many people losing their jobs in all industries. With job losses obviously come lack of funds and/or an unwillingness to spend money on discretionary items, such as dining out and travel. Even those who have not lost their jobs are likely to have lost at least some of their expected income. The concern in the industry is that even when things return to “normal” or even “semi-normal,” discretionary spending will not return to pre-COVID levels for quite a while. In fact, as Globest.com reported, while commercial real estate will likely trail the overall economic rebound, and last anywhere from 12 to 30 months, it is likely that the hospitality industry is facing its own recovery of up to 30 months.

The hospitality industry may attempt to mitigate its damages by invoking force majeure clauses in their loan documents or leases, if in fact such clauses are contained therein. One issue will certainly be whether or not the specific force majeure clause at issue addresses pandemics or other related situations. If not, it is not at all clear whether the current COVID-19 situation will be deemed within force majeure. Certainly the local and federal restrictions on social distancing as well as travel allow for a plausible argument for the invocation of a force majeure clause. Even if force majeure is unavailable, the industry may attempt to utilize other defenses, including impossibility of performance or frustration of purpose. Careful attention must be paid to the operative loan documents and/or leases to determine if COVID-19 qualifies as a “force majeure” event or if there are any other legal doctrines that apply. This requires a detailed analysis of the contractual language, governing law, legal precedent, and the specific facts.

In the near term, COVID-19’s effects on the hospitality industry will likely have a substantial negative impact on many institutions and personnel involved. Borrowers, institutional entities, and small businesses all face similar hurdles, including debt service, rent, real estate taxes, personnel expenses, and health insurance. While certain recurring expenses may be decreased due to furloughs, others (such as rent or mortgage payments) are likely to remain at their pre-COVID-19 amounts and intervals. So the issue becomes — how restaurants, hotels and others in the hospitality industry can try to work with their lenders or landlords during this time.

From what we have seen from our clients (which include financial institutions, CMBS lenders, landlords, and hotel and restaurant owners and operators, by example), and the industry in general, there is no “one size fits all” approach. Lenders and landlords appear to be evaluating each situation on a case-by-case basis, as opposed to implementing a general approach for all loans and leases. The new bankruptcy rules, which went into effect in February 2020 and increased the liquidated debt limit to $7.5 million for Chapter 11 small business filings, should prove helpful to smaller sized restaurants and hotels that need restructuring as a result of COVID-19.

One important lesson gleaned from our legal representation in this industry over the last two cycles, is that every situation is unique, has its own set of nuanced issues, and requires a detailed legal analysis. While there will be many approaches to how the various situations are handled by lenders and landlords, there are likely three main scenarios that will arise. In the first scenario, the lender/landlord will be happy to immediately work with the borrower/ tenant and provide some type of forbearance, either with some amounts forgiven or with catch-up payments either at end of the term or some other period of time. The second and perhaps least common scenario is one in which the creditor is unwilling to work with the debtor as the creditor has its own financial issues to deal with as a result of this all-encompassing pandemic, including debt service, taxes and a myriad of other expenses. The third and perhaps most likely scenario is some type of a middle ground in which the creditor is willing to forbear for a certain period of time if the debtor provides financial information to show the creditor that it is in fact in need of financial assistance due to COVID-19. In our experience, most creditors will at least preliminarily be willing to work with their debtors to help them out of a difficult situation.

Another interesting issue will certainly arise as to how the courts will deal with attempts to foreclose or evict once any governmental prohibitions and forbearance periods have expired. The current scenario is unlike that in 2008 for many reasons, including that in the current situation the default position is not necessarily the debtors’ fault. However, it is not the creditors’ fault either. So, whether it will be the creditor or the debtor who ultimately bears the burden associated with the debtors’ inability to pay will be an interesting issue to watch develop.

Finally, there is no doubt that the end of quarantine will likely result in a huge demand to travel, socialize, and dine out for most. That will likely lead to a small, at first, resurgence in demand for hospitality industry services, which, as more and more of the current restrictions are lifted, will grow larger and larger, and create a boom in the hospitality sector once things have normalized.