Steady Work: Best Restaurant Management Advice from Starbucks’ ‘Playbook’

4 Min Read By Karen Gaudet

In Steady Work, author and former Starbucks’ Regional Manager Karen Gaudet offers restaurant management advice and a heartfelt personal story about how “Playbook,” a continuous improvement business system, revitalized the retailer during the global financial crisis and helped employees in Newtown, Connecticut, get through the worst week of their lives.

It’s relevant today because it helps restaurant leaders contend with enduring issues like crisis recovery, demand fluctuations, food waste, keeping the human touch, managing change, and retaining employees. In this excerpt, Gaudet describes learning how the new system would improve the work of managers, baristas, and support partners.

I was sitting alongside my colleague, a regional director from Chicago, in a Starbucks Seattle headquarters lab waiting for an introduction to the lean operating system they were calling Playbook.

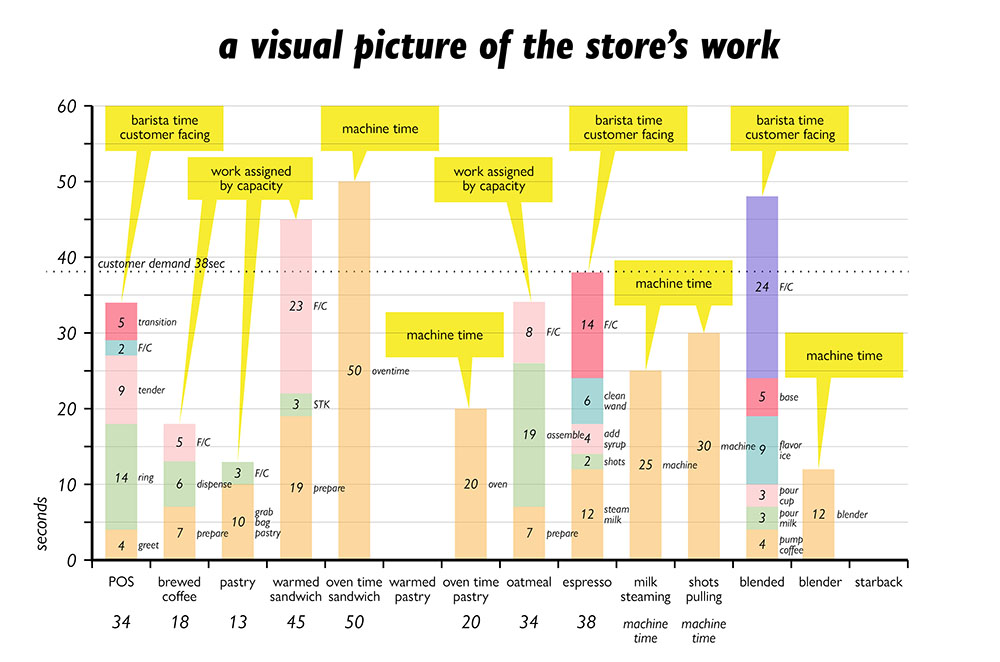

Step one to learning this system was more lean training. We started by making a picture of work that occurred in the stores. With graph paper, rulers, and pencils—and using the data the lean team had been collecting for months—we broke down every task into timed components. We drew familiar work sequences such as brewed coffee.

Next to that, we included the work of warming sandwiches, preparing an oatmeal breakfast, creating a blended drink, etc. We color-coded the sequences, using red for machine time and blue for people time. We had drawn work sequences before, but this was different. Now, we were looking at all the interconnecting work of everyone in a store, the way it really happens. In fact, the illustration below was based on POS data collected from a Starbucks cash register in Chicago, plus time and motion studies conducted by the lean team.

After we spent two hours learning how to break down work into components and then build a story of customer demand, we were ready to see how we might use this information to make staffing decisions—including how many people on each shift and everyone’s roles in 30-minute increments throughout the day. The lean team referred to these decisions as “calling the play.

Our stores could be radically different from one another. Some were drive-through stores off major highways with steady, near-constant demand; some stores were for commuters and had big spikes in traffic; others were community stores that relied on personal attention and community building and had many micro spikes and valleys in demand throughout the day.

That meant our managers needed to know how to staff their stores for typical days and then be able to rewrite plays for atypical days when there was road construction, bad weather, a local epidemic of the flu, or a tragedy like the shooting at a school in Newtown, Connecticut. Plus, managers needed to know how to write a play so that they could teach it all—theory and practice—to new leaders in training.

For a few weeks before our meeting, the Seattle lean team had been working on this problem with a couple of local baristas. Together, they broke down the work of baristas, cashiers, and floaters and then built standardized work routines for everyone that would allow people, when needed, to work at faster cycle times because they had fewer components to their jobs.

Prior to this, store partners did a lot of ad hoc work. If milk ran out, the barista would get a new gallon or ask the cashier to get it for them. If the cashier had time, they would usually be warming sandwiches or performing a dozen other “fetch” activities, besides taking orders. This was fine until orders went from about one every 60 seconds to one every 20 seconds.

In the new standardized routine, when a store entered a rush hour, the shift supervisor or manager would call for a new play. For this hour, the barista might work the two-beverages-at-once cycle. They would remain focused only on that task. The cashier would focus solely on greeting customers, then taking orders and money — no warming sandwiches or restocking.

The floater was renamed store support and given new standardized work. They would make brewed coffee every eight minutes, replenish supplies for the barista and cashier based on simple visual cues, and take on many of the cashier’s fetch duties, all in a repeated routine.

The lean team brought us into the lab—a full-scale mock-up of a store—and introduced us to the local baristas they had been working with. Using POS data from a very busy downtown Chicago store, they began sending people through the line with orders at a real-world, rush-hour clip.

I stationed myself at the espresso bar to watch the action and almost immediately fell into a conversation with the barista while she worked steadily through her line of cups, producing one beverage after another. When she ran low on whole milk, she threw the red cap off the gallon of milk into a clear plexiglass cube and returned to her measured two-beverage cadence. The support partner collected the replenishment signals out of the Plexiglas cube about three minutes later and then returned with the gallon of milk.

After 15 minutes, the demonstration ended, and I looked up in surprise. The barista—working at a much faster pace than normal— had been chatting with me the entire time. I asked how she managed to do that, and she smiled. “I’m just doing this one thing,” she said. “I can work faster when I keep my focus.”

In fact, everyone could work more efficiently while single-tasking for a definable period, such as a morning rush. After the rush was over, the shift supervisor could call a new play and give everyone a chance to move around in a different way.

I was convinced.

To learn more about Steady Work, click here.