Hospitality’s $2.5 Billion Brawl

4 Min Read By Marty Hahnfeld

Ask any hotel industry executive to describe the biggest misstep in their industry over the past 20 years and it’s a safe bet you’ll get the same answer: Hotel brands didn’t understand the significance OTA’s would play quickly enough, and once they did see the big picture, they didn’t act forcefully enough to take control of the situation.

Will history repeat itself in the restaurant industry? Not if brands take control now.

Yes, we’re talking about hotels. Why? Because it’s hugely relevant and the table is set for the restaurant industry to end up in the same situation.

Let’s start with the basics. OTA is an acronym for “Online Travel Agent”. You’ve likely used one to book a room or airfare by using sites like Expedia, Orbitz, or Booking.com — all popular OTA’s (there are dozens more).

The OTA’s got their start in the mid-1990’s by marketing, mostly, what was considered surplus hotel room inventory. They charged brands a hefty 10-20 percent commission for each booking, and since the bookings were considered largely incremental, the hotels were happy to pay. After all, an empty hotel room is the purest expression of perishable inventory. So far, so good… right?

In 2004, things began to change. After Google OK’d the use of trademarks as advertising keywords, even if the advertiser didn’t own the trademark, the OTA’s pounced. By quickly taking advantage of these new guidelines, OTA’s launched expansive digital advertising campaigns using the hotel brand’s own trademarks and amassed huge consumer bases. Their market share skyrocketed. Then, commissions increased. Then, commissions increased again. And, again.

Think it can’t happen to the restaurant industry? Think again.

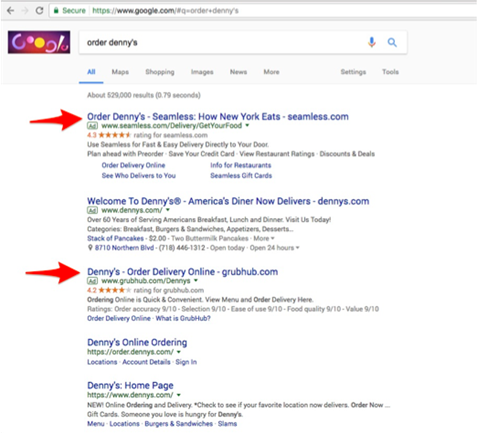

A Google search for “order Denny’s” displays a Seamless (Grubhub) ad ahead of Denny’s own digital ordering site.

By 2010, OTA’s were booking in the ballpark of 20 percent of all hotel rooms in the US, and the brands (now, fully enlightened) began taking steps to reclaim consumers. OTA’s and hoteliers had become, in the truest sense of the expression, “frenemies” — frustrated with one another’s tactics, but increasingly reliant on each other to meet their respective goals. Brands launched comprehensive (read: expensive) campaigns to recapture consumers by stepping up their in-house e-commerce capabilities, and by offering loyalty programs and discounts only available directly. They also took their tensions to courtrooms and the corridors of government, arguing and maneuvering to restrict one another via rules and regulations.

Fast forward to 2017 and the song remains the same. OTA’s control, in the ballpark of, 30 percent of hotel bookings (that’s nearly 70 percent of bookings made digitally!). And, when all is said and done, OTA commissions cost the industry in excess of $2.5 billion annually. The advertising, courtroom, and regulatory battles continue, and most experts predict that despite the brands’ efforts to rebalance the equation, OTA’s will gain even more share over the coming years.

So, does any of this sound familiar yet? If not, let’s complete the analogy:

Restaurant marketplaces, like Grubhub, Postmates, and DoorDash are the food equivalent of an OTA. Most use inexpensive delivery as a consumer acquisition tool and charge commissions of 20-30 percent to the restaurants. They already control significant portions of the small chain and independent landscape (especially in the ‘NFL cities’). And, like the OTA’s, they position themselves as bringing incremental sales to a brand by promoting a brand’s offerings to their (the marketplace’s) loyal consumers. At the foundation, this all holds up, many consumers visit marketplace sites first when they’re hungry. Today, a cheeseburger, tomorrow ramen, the next day a burrito — marketplaces have many choices on display for every craving.

But, without control and wisely structured agreements, the marketplaces have ample opportunity to take advantage of the industry, just as the OTA’s did in 2004. Here’s the short list of smart steps every brand should take to gain the most, and lose the least, while employing marketplaces as a sales channel:

- Make sure your own, branded, e-commerce sites and apps are world class so that your most loyal consumers love ordering directly and won’t be tempted to order elsewhere because of a better, faster, or more accurate user experience. Utilize a service like Olo’s Dispatch to offer delivery via your own sites and apps. Make sure that the marketplaces that are delivering your food when someone orders from their apps and sites are equally willing to deliver for you when a guest comes to your sites and apps.

- Be tough but fair in your agreements with marketplaces. Prohibit them from using your trademarks in any advertising (after all, it’s not an incremental consumer that goes looking for how to order food from your brand). Demand lower commissions for any sale that is demonstrably a prior customer or began their search on your site.

- Demand marketplaces fully integrate to your in-store systems and operations so that you have the ability to understand throughput from the marketplaces by geography, by day-part and by food type. This is also important in franchise systems where marketplace orders that are received on ‘out-of-band’ tablets can be ‘forgotten’ and not entered into POS.

So, that’s the $2.5 billion conundrum. Where it goes from here depends on each restaurant’s commitment to furnish great e-commerce sites to its customers, offer delivery as an option to its existing customers through its own e-commerce channels, and demand even-handed and tightly integrated partnerships with every marketplace.